Adipose-derived stem cells have fastened the pace of research on regenerative medicine with their minimally invasive extraction and accessibility to the high quantity of stem cells. Stem cells have been a key area of research for tissue reconstruction and damage repair. Numerous disorders lack adequate treatment options owing to the lack of regenerative therapies. Stem cells have boosted these therapies, which are particularly useful in cases of severe tissue damage. Adipose stem cells offer a better alternative, and several clinical trials have been exploring their applications in various diseases.

Adipose-Derived Stem Cells

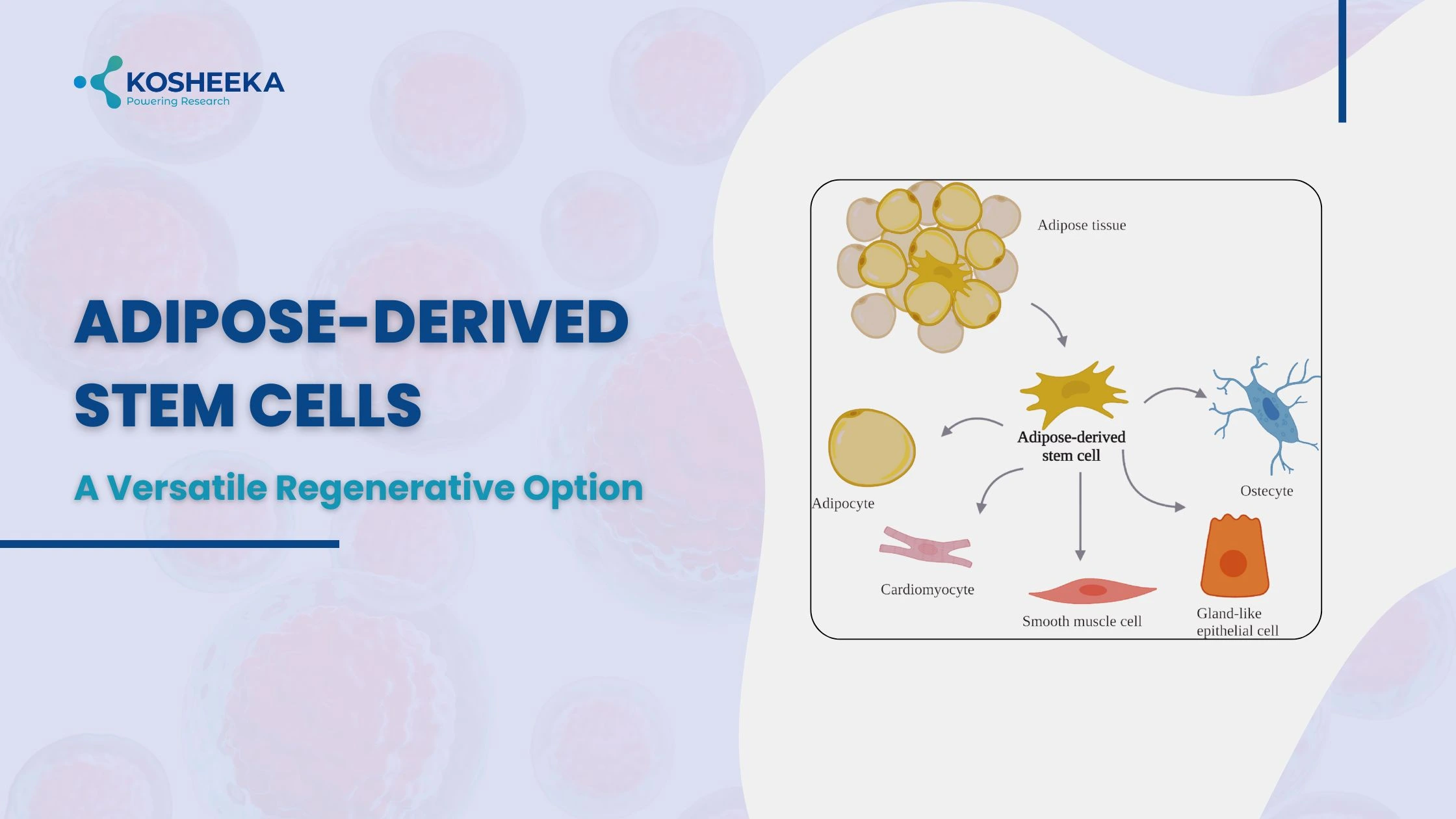

In 2001, adipose tissue was identified as the new source of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). These cells, also called adipose derived stem cells, showed promising prospects due to the abundance of adipose tissue. Adipose tissue is the fat storage area present commonly in subcutaneous, visceral, and muscular regions. Their ubiquitous presence of adipose tissue enables the harvesting of stem cells in high quantities without complications.

Subcutaneous is the frequently employed source of human adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) isolated from the abdomen, arms, and thighs. Their characteristics vary with their location. For example, ASCs from superficial abdominal regions exhibit less apoptosis than those from arms. Their location within the tissue is debatable and is considered either near or within vessels. Despite their mesodermal origin, ASCs have shown differentiation into myogenic, neural, and cardiovascular lineages, demonstrating their potential in therapy.

The Isolation Process

The isolation procedure employs an enzymatic digestion method. Extraction of adipose tissue follows washing with buffer and subsequent incubation in collagenase type II enzyme solution. The enzymatic digestion results in a cell pellet, known as stromal vascular fraction (SVF). The addition of the culture medium in the following step deactivates the enzyme. Washing the cells and resuspending them in hypotonic NH4Cl or NaCl solution remove erythrocytes.

Subsequent filtering of SVF through a mesh separates the tissue fragments. After a final washing step, plating SVF in a culture medium and CO2 incubator results in the emergence of different cell populations, including preadipocytes, endothelial cells, ASCs, immune cells, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, etc. However, ASCs adhere to the culture dish, and other cells can be washed out to obtain ASCs. They are spindle-shaped with a doubling time of approximately 2-5 days.

Characterization of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells

Isolated ASCs are not a homogeneous population and require proper characterization. The International Society of Cellular Therapy has defined the criteria for ASC identification by adherence on a plate, expression of makers, and low or negligible expression of negative markers. The positive markers include CD106, CD90, and CD73, with more than 80% of cells expressing CD44, CD29, and CD13. The negative markers belong to the hematopoietic lineage, such as CD34, CD11b, CD45, HLA-DR, CD19, CD31, and CD235a. Additional verification can occur through functional assays that evaluate the ability to differentiate into preadipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes.

However, during the first passage, ASCs exhibit CD34 expression, which reduces with passage number. By the second passage, they lose hematopoietic markers and gain mesenchymal markers. Therefore, passage 2 provides a more homogeneous ASC population. The ASC cryopreservation does not affect their potency, thereby promoting their use in cell culture research.

Applications of Adipose Derived Stem Cells

In 2004, the first clinical trial report using ASCs surfaced. It demonstrated their therapeutic benefit in a 7-year-old girl with calvarial defects. These cells have also shown anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. These properties effectively treated refractory graft-vs-host disease by administering allogeneic ASCs. Additionally, they migrate toward injury and tumor tissues, indicating their role in delivering therapeutics to tumor sites. ASCs, therefore, have promising potential in the treatment of disorders. Below are a few applications of these cells.

Wound Healing

ASCs secrete numerous growth factors that mediate paracrine signaling to induce tissue healing. Additionally, they promote wound healing by recruiting immune cells and stimulating angiogenesis by growth factors such as GCSF, EGF, VEGF, FGF, etc. Animal studies have shown reduced scar size after ASC infusion. Their combination with scaffold improves their potency and survival in the tissue. ASC media provides a cell-free alternative in wound healing. Thus, ASCs could treat diabetic wounds, burn scars, skin injuries, and ulcers.

Bone Regeneration

ASCs can differentiate into osteoblasts and chondrocytes that can treat bone disorders. They have shown repair of defects in cartilage and maxillofacial defects. These cells also release, such as FGF, MMP, BMP2, etc., that stimulate bone formation. Furthermore, seeding ASCs on scaffolds has yielded improved bone structure and characteristics. Adding growth factors and miRNAs to scaffolds that signal ASC differentiation can also improve the outcomes. Many synthetic, natural, and composite materials have been utilized for bone regeneration. Each has its own pros and cons. Clinical trials have proven their effectiveness with scaffold. However, the procedure requires further standardization.

Nervous System Regeneration

ASCs can differentiate into neurons and Schwann cells that support neuronal functions. Furthermore, ASCs also secrete neurotrophic factors such as BDNF, GDNF, IGF1, FGF, etc. Differentiated neurons express more neuronal markers and have higher proliferation rates than other stem cells. The anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory properties of ASCs also stimulate nerve repair.

They also increase the ratio of M2 to M1 microglia to alleviate neuroinflammation. ASCs also release exosomes that downregulate NF-κB and MAPK signaling that cause inflammation. ASC therapy has shown functional recovery in spinal cord injury models. These cells have displayed increased myelin fibers and better nervous tissue organization in peripheral nerve injury. Neurological disorders do not have an absolute cure. ASCs can prove to be a potential treatment for such disorders.

Cardiovascular Disorders

Cardiovascular disorders have been a predominant cause of mortality and comorbidities. The studies have shown positive outcomes with ASC therapy. ASC differentiates into cardiomyocytes and releases anti-apoptotic, angiogenic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic factors. ASC administration resulted in a reduction in myocardial infarct size, improvement in cardiac function, and the formation of blood vessels.

However, the outcomes vary depending on the administration route. More strategies, such as genetic engineering of ASCs, use of extracellular matrix with cells, stem cell priming, etc., have yielded favorable results. ATHENA and APOLLO trials at phase I and II showed a reduction in cardiac scar size. Further research and trials can provide more accurate results.

Liver Regeneration

Ischemia-reperfusion injury is a common postoperative complication of liver surgery. ASC transplants have exhibited increased antioxidant activity and a decline in injury-related biomarkers. They also secreted regenerative factors and suppressed inflammatory cytokines, thus mitigating the damage. In large animal models, ASC treatment showed improved liver function and structure. In liver cirrhosis, it decreased liver fibrosis by apoptosis of myofibroblasts and reducing oxidative stress. Therefore, ASCs can offer promising therapy for liver disorders.

Conclusion

ASCs can differentiate into non-mesodermal cells, which has broadened the scope of stem cell therapies. Additionally, their abundance has substantially augmented their use in research and clinical trials. Early studies have shown positive results with ASC administration. However, procedural standardization remains a key step in their translation to hospitals. More research might improve their therapeutic potential. Kosheeka accelerates this research by delivering human ASCs with ensured quality and purity.

FAQs

Q – Where are adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) extracted from?

They are isolated from adipose tissue present in subcutaneous and visceral regions. The isolation is primarily conducted from the subcutaneous arm, thigh, and abdomen regions.

Q – Which cells do ASCs differentiate into?

ASCs are mesodermal cells that differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic lineages. However, they have also demonstrated conversion into cardiomyocytes, muscle cells, neurons, and vascular cells.

Q – What are the markers for ASCs?

Positive markers of ASCs are- CD106, CD90, CD73, CD44, CD29, and CD13. The negative markers include CD34, CD11b, CD45, HLA-DR, CD19, CD31, and CD235a.

Q – Is characterization by markers sufficient for ASC identification?

Functional assays that test the ASC differentiation into preadipocytes, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts should also be conducted for ASC identification.