The initially identified human bone marrow stem cells were hematopoietic stem cells. In 1976, Friedenstein et al. isolated bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), turning the tide of stem cell research. During in vitro studies, these cells showed differentiation into osteogenic, chondrogenic, adipogenic, and myogenic lineages depending on their medium. Further research revealed the ability of MSCs to form endothelial cells and neurons. Therefore, scientists began decoding the signaling pathways and the cues that can regulate MSCs differentiation.

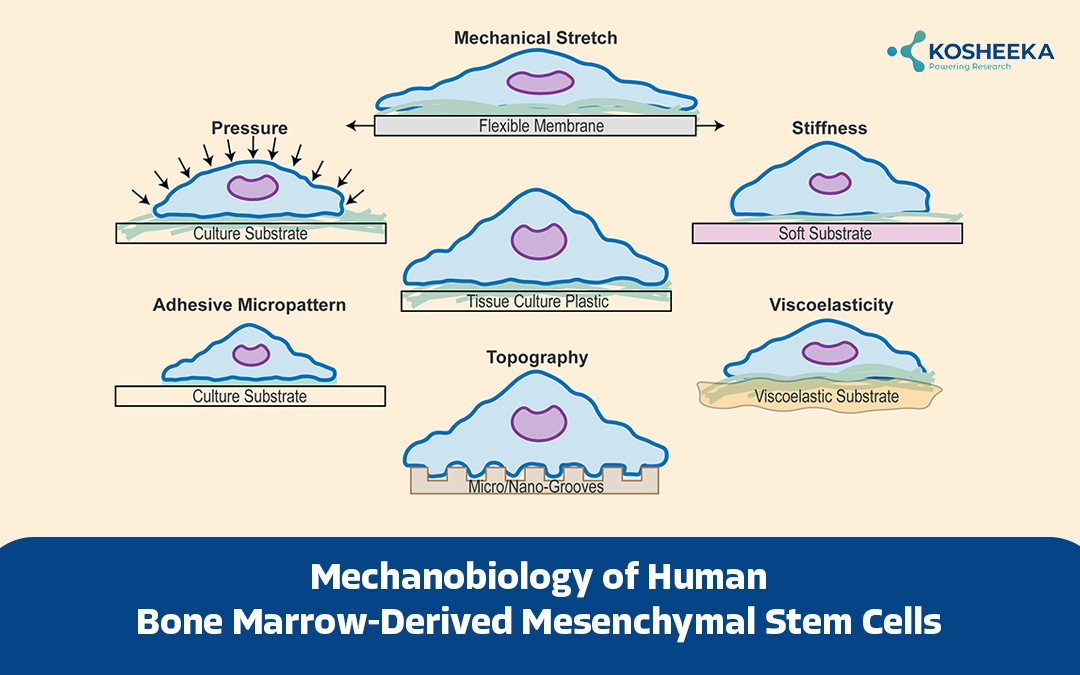

Among them, mechanical stimuli turned out to be a key determinant of stem cell fate. Tissues often encounter dynamic mechanical signals in the form of compression, tension, shear stress, etc. Stem cells convert these physical or mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals to regulate cellular processes. The mechanobiology of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells has garnered interest for research and therapeutic purposes.

Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Since their discovery, progress on mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow has rapidly advanced. The International Society of Cellular Therapy has established a panel of identification markers for these cells. While hematological and endothelial markers including CD45, CD34, CD11b, CD19, HLA-DR, CD79, and CD14 are absent in MSCs, they should express CD90, CD73, and CD105. The identity of MSCs is further confirmed by functional assays that evaluate their differentiation.

Scientific studies have described their anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory properties with application in therapy. The low immunogenic risk of these cells has promoted their use in therapy. Ongoing clinical trials have been employing Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell therapy for tissue regeneration, mostly yielding positive results. However, the majority of the studies allude to the paracrine mechanism of tissue regeneration of these cells rather than direct differentiation of human bone marrow stem cells. It has compelled investigation into their differentiation.

Mechanobiology of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Bone Marrow

The area of mechanobiology deals with sensing mechanical cues (mechanosensing) and transforming them into biological signals (mechanotransduction). Cells, particularly stem cells, reside in a specific microenvironment or niche. In addition to cell-cell interaction, mechanical or physical forces from the extracellular matrix also regulate stem cell quiescence, proliferation, and differentiation. These forces include matrix rigidity, cell adhesion, matrix topology, shear stress, etc. For instance, a stiff surface redirects MSC differentiation towards osteogenic lineage instead of adipogenic lineage. On the other hand, a study showed that a soft matrix promotes the expression of chondrocyte-specific genes even in the absence of a differentiation medium. The effect of cell shape is evident when rounded MSCs undergo chondrogenesis.

Components of Biomechanical Machinery

Three crucial proteins constitute the biomechanical sensing and signaling-

Cell-Matrix Adhesion Proteins

They include transmembrane proteins – integrins and cadherins. Integrins move through the membrane to form clusters, also known as focal adhesions. These are dynamic structures that form in response to matrix rigidity and topography. Assembly of focal adhesion activate MAPK, focal adhesion kinases (FAK), paxilin, GTPases, etc. By linking the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix, these proteins transfer mechanical stimuli from the matrix to the cells. N-cadherin associates with β-catenin to favor chondrogenesis. However, fluid flow weakens this association, which allows β-catenin to induce transcription of osteogenic genes.

Cytoskeleton

Cytoskeleton comprises actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments. It spreads the mechanical tension from focal adhesions to cells and vice-versa. Several cues, such as ligand density and substrate rigidity induce cytoskeletal tension. It, in turn, impacts focal adhesion, affecting cell-cell interaction and shape. Filamentous bundles of F-actin and myosin compose stress fibres. They generate contractile forces and transfer them to the focal adhesions. Reducing cytoskeletal tension has demonstrated an increase in Sox9 and PPAR expression in MSCs. Similarly, inhibition of F-actin polymerization of myosin alleviates cytoskeletal contraction and induces adipogenesis over osteogenesis.

Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

ECM contains collagen, elastin, glycosaminoglycans, and proteoglycans. Its composition defines the viscosity and topography of the matrix. For instance, collagen and elastin confer tensile strength and elasticity. A change in the ECM composition alters its geometrical shape, altering the Stem Cell phenotype. Stiffer ECM augments FAK, ROCK, and ERK activity. ECM stiffness also regulates stress fibre density and actin assembly, which affect MSC spreading.

Another piece of this process is stretch-activated ion channels that can modulate ion concentration and impact cell signaling. For example, inhibition of ion channels suppresses myogenesis.

Applications of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy

The growing use of encapsulation technology and scaffolds along with MSCs. Altering stiffness of these moieties can define the lineage of MSCs. Therefore, principles of mechanobiology have been explored in disorders and how they can be exploited for therapy.

Bone Regeneration

Studies indicate that MSCs sense and convert the mechanical cues in joints into biological signals that lead to inflammation. This process has vital implications in arthritis. Exploiting this inference, Zhang et al. fabricated a scaffold from the ECM of MSCs stimulated by compression. This scaffold exhibited the ability to polarize macrophages from M1 to M2 phenotype, minimizing inflammation and promoting bone repair. It suggests that compression stimulates MSCs to secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines. In a similar manner, stretching induces VEGF secretion from MSCs, which in turn increases the release of BMP2 and IGF1 from endothelial cells.

Cardiovascular Tissue Engineering

A study documented that three-dimensional (3D) culture on a substrate of low compressive modulus and in the presence of VEGF transformed MSCs into endothelial cells. Nanotopographical features of the substrate have driven cardiac differentiation of MSCs, which has the potential to treat myocardial infarction. Studies have also shown that cells align on stretched polymer films rather than the unstretched ones, inclining towards cardiac and myogenic lineages. Cyclic mechanical strain enhances the expression of tropomyosin and α-actin of cardiomyocytes in MSCs in the presence of TGFβ1. Typically, TGFβ1 induces osteoblast formation from MSCs. Research has depicted that both the magnitude and frequency of strain influence the cardiomyocyte-specific gene expression. Another study illustrated that mechanical and electrical stimulation in the presence of a myocardial scaffold and chemical factors can develop cardiomyocytes from MSCs.

Conclusion

For decades, stem cell differentiation has been a subject of mystery. The microenvironment or niches have been defined to control the stemness. Despite much research, the biological signaling pathways remain elusive, while mechanical cues from the 3D niche are overlooked. In the past few years, several studies have established the role of physical forces in cell survival and proliferation, particularly for stem cells. It has introduced the novel field of mechanobiology. The field has garnered interest for regulating MSC differentiation.

The utilization of scaffolds and encapsulation has already become common in MSC therapy. Therefore, researchers are advancing further by tuning the properties of the scaffold. It is paving the way for substrate-mediated differentiation without the addition of specific growth factors. This approach can transform the treatment of several disorders and open new avenues. Kosheeka has been aiding this transformation by offering high-quality Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells.

FAQ’s

Q-What are human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)?

They are multipotent cells that differentiate into various cell lineages such as bone, cartilage, fat, muscle, endothelial cells, and neurons. They also possess anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory properties, making them valuable for regenerative therapies.

Q-How do mechanical stimuli influence MSC differentiation?

MSCs convert mechanical signals such as compression, tension, and shear stress into biochemical signals through mechanosensing and mechanotransduction. They regulate MSC quiescence, proliferation, and differentiation pathways.

Q-What role does the extracellular matrix (ECM) play in the MSC function?

The ECM provides the physical environment affecting MSC behavior. Its stiffness, composition, and topology influence MSC differentiation, where stiffer matrices favor bone formation and softer matrices support cartilage production.

Q-How is mechanobiology applied in MSC-based therapies?

Principles of mechanobiology guide the design of scaffolds and encapsulation techniques to direct MSC differentiation without added growth factors. This strategy is used in tissue engineering to enhance therapeutic outcomes.